Introduction - Tomorrow's Houses

Introduction

But New England, at least, is not based on any Roman ruins. We have not to lay the foundations of our houses on the ashes of a former civilization —Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Thoreau"

What does architecture amount to in the experience of the mass of men? I never in all my walks came across a man engaged in so simple and natural an occupation as building his house. —Henry David Thoreau, Walden; or, Life in the Woods

It seems a curious Town- Some Houses very old, Some-newly raised this Afternoon —Emily Dickinson

I have a great sense of the Puritan, that rich people especially should do something. —Philip Johnson

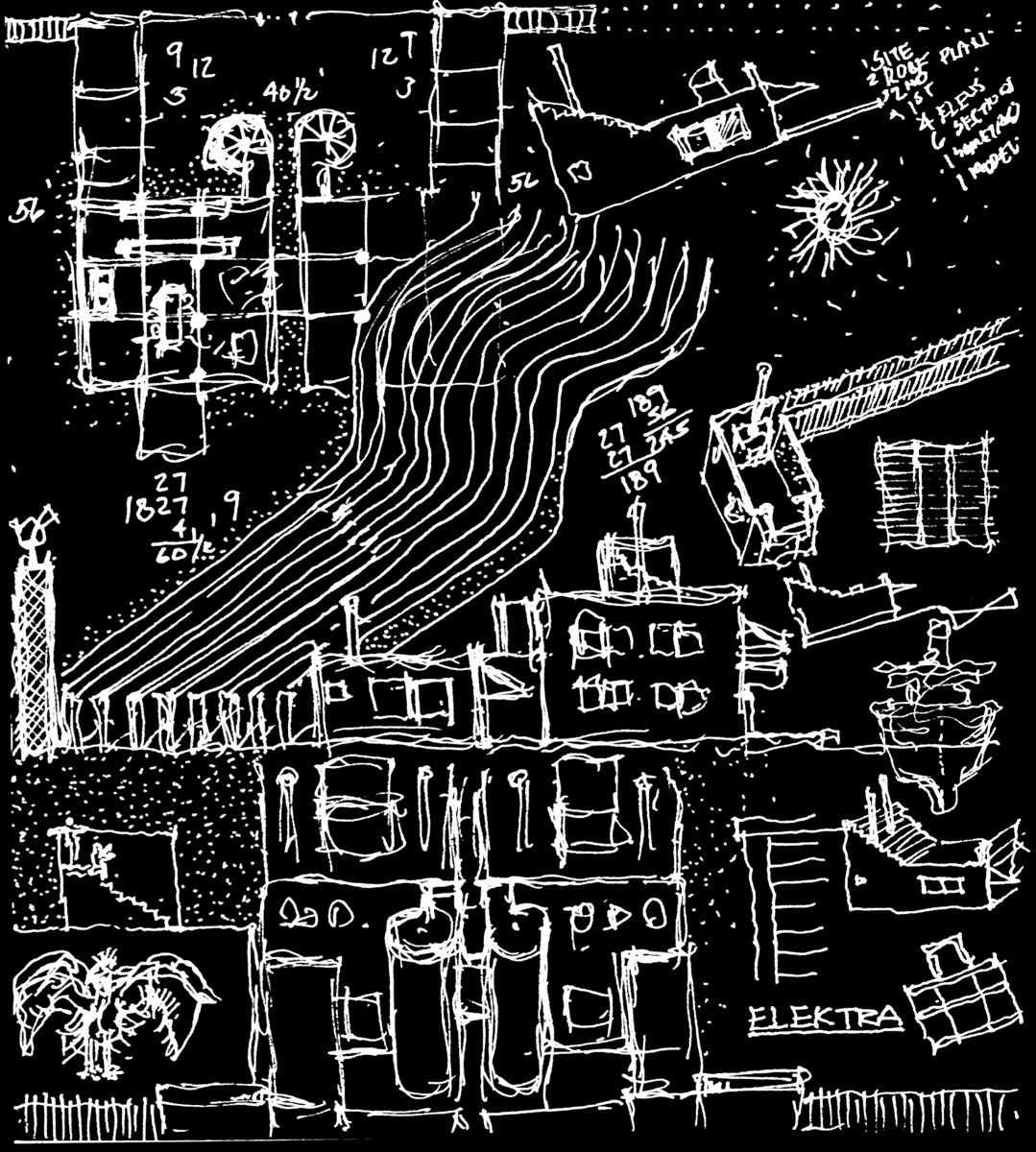

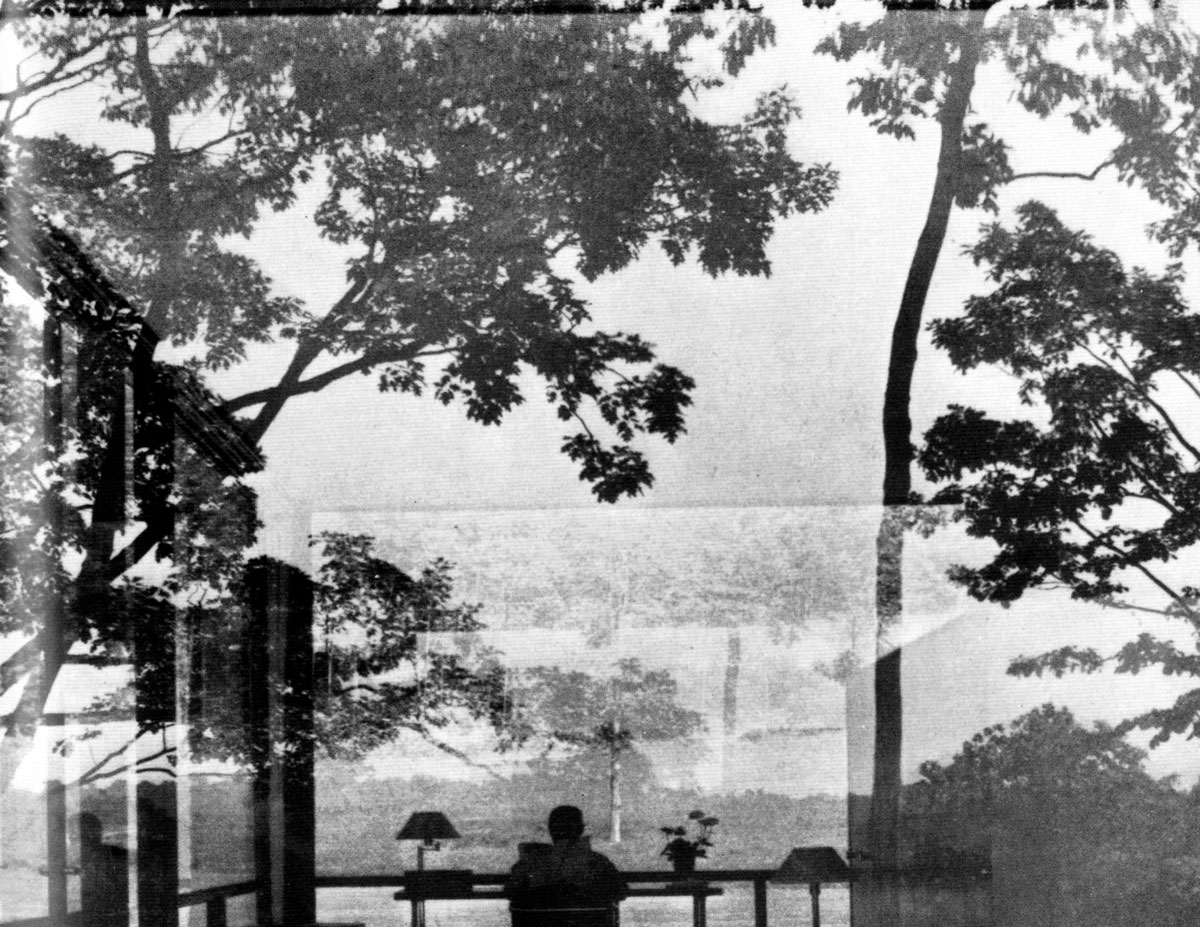

Thanks to Philip Johnson, my first house was built after a memorable visit to his Glass House in New Canaan. My clients in nearby Bedford, New York, were an august magazine editor and a distinguished surgeon who were invited to Philip's estate not only to see his famous house but also to show him a model of the new home that I had designed for them. Philip, in his tradition of generosity toward young architects, exclaimed to the surgeon, "At your age, what better way to spend your money? Build the house right now!" They did exactly as Philip said, and my career was under way. I remember sitting in the house as twilight fell, all together in a room with few lights on. Soon, all of us were black silhouettes framed against the sky, reflected in the large glass walls. Over a fifty-year period the architect and chief occupant of that magnificent house reigned over modern architecture in New England. In the beginning his influence helped it to grow, and then later he was instrumental in its demise.

My work as an architect has long been inspired by the modestly heroic houses of New England of the mid-twentieth century. Exquisitely balancing geometry and nature, the architects Marcel Breuer, Eliot Noyes, and Philip Johnson, among others, reinterpreted native traditions such as the ancient stone walls of forgotten farms as essential elements of their compositions. These spartan, cubic homes, set in a clearing in the woods, were balanced combinations of contrasting materials: wood, stone, and glass. But while these houses referred to an idealized past, they also proposed a gleaming future of optimistic living in close physical and visual proximity to nature. They are humanly scaled, luxurious in their restraint, and emblematic of a desire for living in harmony with the natural environment that is current once again.

Why did modern architecture take root in this region of colonial homes and entrenched tradition? Did the International Style adapt in any way to the history and building traditions of the region? And most importantly, why did the grand experiment in many ways fail, so that today the vast majority of homes built in New England are of the very same styles-Georgian, colonial, and neoclassical- that the early modern architects pronounced dead as early as the 1930s?

The unlikely emergence of modern houses in New England, a region long known for its traditional houses and conservative architecture, was a perfect storm of events. Although a few modern homes were built in the 1930s, the movement did not gather steam until after World War II and the explosion of suburban construction for the returning soldiers in the bedroom communities around Boston and New York. Focusing the energy of modernism were a number of fortuitous events; foremost was the arrival at Harvard in 1937 of the architect Walter Gropius, the former director of the avant-garde Bauhaus school of architecture. Gropius emigrated to London after the Nazis took power in Germany and closed down the Bauhaus, a powerhouse of modernist thought whose goal was the convergence of industry and the arts, including architecture, sculpture, painting, and industrial design. Gropius soon left London for America, bringing his colleagues Marcel Breuer and Josef Albers and the modernist mission to these shores.

Then there was the presence of Philip Johnson, the unique combination of architect, curator, writer, and wealthy patron of the arts who had organized the 1932 "International Style" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Deciding to practice what he preached, Johnson went to Harvard to study under Gropius. After the war, he set up practice in New Canaan, Connecticut, along with a number of fellow Harvard graduates such as Eliot Noyes and John Johansen Through the influential salons he organized at his canonical Glass House of 1949, modern architecture was promoted at exactly the right time and place, when the area was ripe for new ideas to flourish and ambitious new projects to be built. The subsequent flurry of activity reached its peak in the 1950s and 1960s, then subsided, leaving behind a remarkable number of avant-garde houses that are landmarks in the development of modern residential design, not only in New England but worldwide. The landscape of forested hills and the open fields of abandoned farms became a petri dish for the development of the modern home. The intellectual landscape also served the modernist cause, following a long history beginning with Ralph Waldo Emerson, who advocated in the early nineteenth century an authentic and original American art and architecture. Henry David Thoreau's philosophy championing simplicity and living in harmony with nature was also important, as was a characteristically Yankee tolerance for eccentrics in the woods. Frank Lloyd Wright made a cameo appearance from the Midwest, as did virtually all the major characters of modern architecture, including Mies van der Rohe, Josep Lluis Sert, and Le Corbusier in his only built work in the United States, the Carpenter Center at Harvard. Among the bohemians, the sculptor Tony Smith built two houses in Connecticut before he gave up architecture to devote himself fully to sculpture.

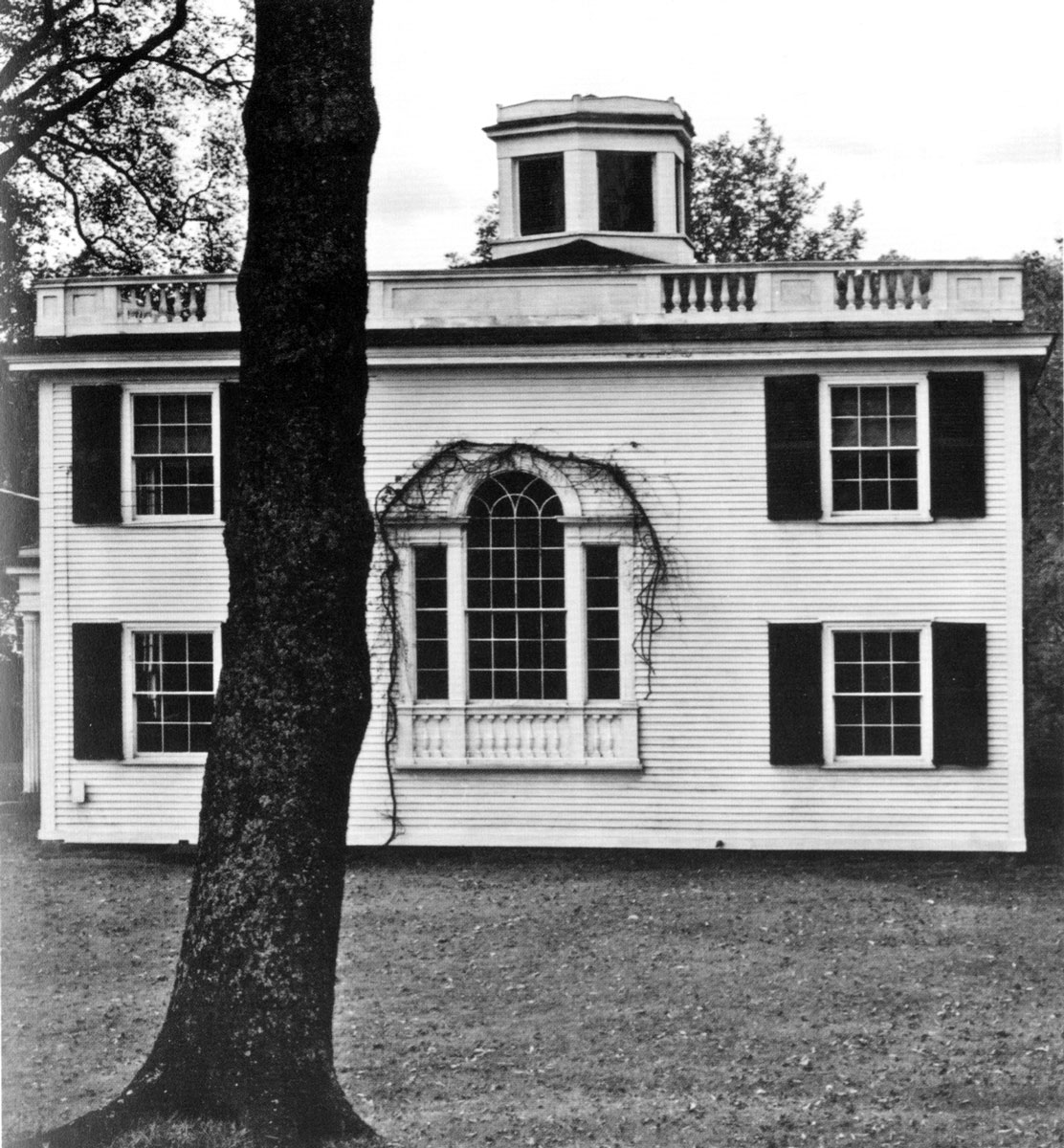

Ironically, this flourishing of modernist form occurred in one of the oldest regions of the country, and the one that not only laid claim to the establishment of the idea of the United States but was equally proud of its century-and-a-half, pre-Revolutionary War history, including that period's architecture. Twice as old as the nation, with traditions reaching back to 1620, New England boasted a population who considered their golden age of architecture to have concluded by 1776! By the time modern architecture emerged fully mature in Europe during the 1920s, the area had, in 1910, already established one of the earliest landmarks preservation groups, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, now called Historic New England. But despite the regional emphasis on history, modern residential architecture flourished during the 1940s and 1950s in New England as a surprising counterpoint to new architecture in California. Since the 1848 Gold Rush, California was the land of the unexpected, of reinvention, the source of fantasies concocted by Hollywood. European emigre Richard Neutra imported modernist ideas of space and new ways of living in the Lovell Health House, its International Style white cubic profile complementing the sun-drenched Los Angeles hills. (In the 1920s Frank Lloyd Wright also built a number of modern houses of an opposite sensibility: darker, heavier, more like man-made mountains, and inspired by Mayan temples and the exoticism of the cinema.)

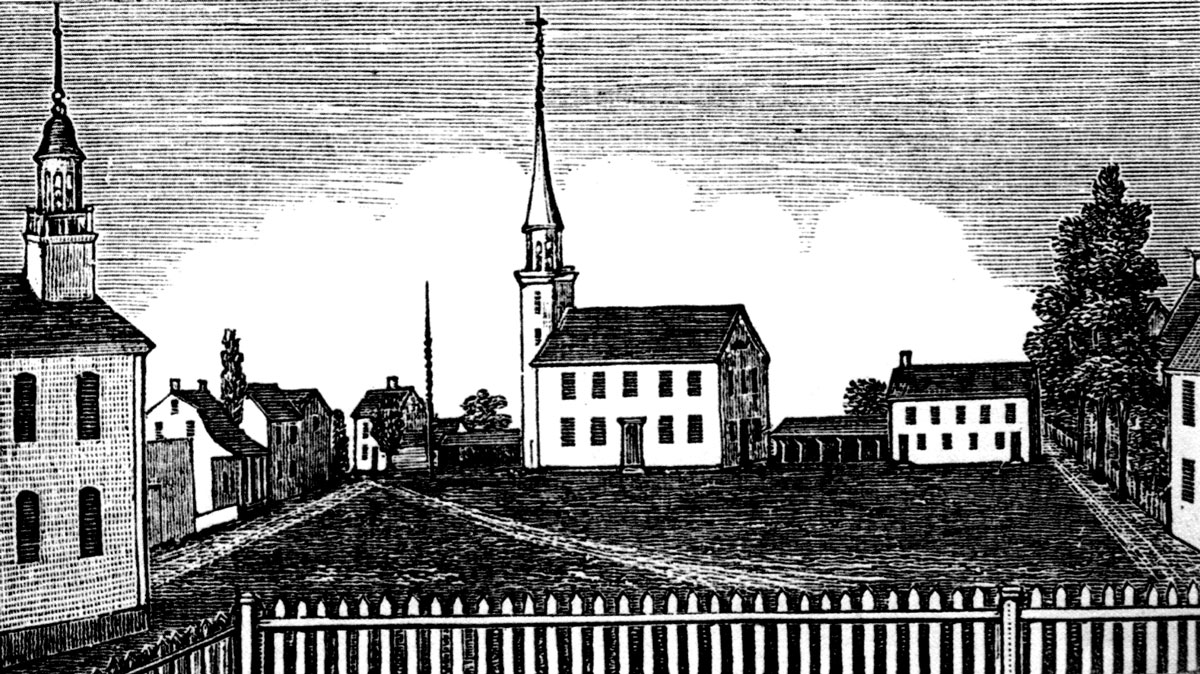

New England's climate, on the other hand, offered "harshness of contrasts and extremes of sensibility—a cold that froze the blood, and a heat that boiled it," as Henry Adams wrote in his Education, a climate not obviously suitable for the outdoor living spaces encouraged by modern houses. Thoreau related in his book Cape Cod that the region was explored first by the French and then by Captain John Smith, who considered it an extension of the Virginia Colony further south. By the time the Puritans landed on Plymouth Rock in 1620, most of the Indians had already died of diseases brought on by the English . What was once a robustly settled area became a "howling wilderness," as described in 1654 by Edward Johnson in his history of the founding of New England. So called captivity narratives, such as that of Mary Rowlandson, recounted a time of English settlements on an edge of a vast, unknown, and terrifying interior, as Arthur Miller describes in The Crucible: "The edge of the wilderness was close by. The American continent stretched endlessly west, and it was full of mystery for them. It stood dark and threatening." The Puritans saw themselves as pilgrims to a "New Israel," a promised land away from the persecutions in England. They gave their towns names redolent of the Bible: Salem, New Haven, New Canaan. The nine-square-grid plan of New Haven, the colony that John Davenport established as a new order in the wilderness, was based on Ezekiel's vision of the Temple in Jerusalem. The legendary achievements of the region's founders were always at the forefront of collective memory. When Hawthorne wrote The Scarlet Letter in 1850, he referred to a history already two hundred years old. There were constant revivals of an ideal colonial period of heroic achievements. Even the perfect and picturesque white New England village was an invention of the nineteenth century, a re-creation of an idealized settlement that did not exist in the time of the Puritans. Its definitive form was established in the pages of Yankee magazine and in Wallace Nutting's 1920s photographs of colonial interiors with models in traditional garb. Walter Gropius used this utopian image as a model for architecture and urban planning in his 1944 essay "In Search of New Standards of Design": "What was the design secret of a New England town of old? The comforting repetition of form elements and colors. For it provided that neutralizing background of a simplified order with which features of real importance for the community could be clearly contrasted by accentuated emphasis."

The idea of modern architecture taking root in an area of well-established tradition was similar to the rise of the new architecture in hidebound Europe. As in Europe the past was to be swept away by the new style, appropriate as it was to present-day conditions of technology and living. Modern architecture in New England was somewhat kinder and gentler, with a typically American absence of the ideology that characterized the European movement's numerous manifestoes and propagandistic slogans, such as Le Corbusier's "Architecture or Revolution" However, Philip Johnson himself confessed, "I was terribly, terribly Puritan, still am." And like the Puritans, architectural modernism, once established, then ruled with great intolerance until it too was overthrown, in the 1970s, helped on by the apostasy of Johnson, who embraced historical architecture with a vengeance, ushering in the reign of postmodernism during the 1980s.

The Puritans, despite their general intolerance, did promote literacy and study through the founding of the major liberal arts institutions Harvard and Yale, which would be the academic homes for many of the immigrant modern architects. They were the scenes of important intellectual discussions about modern residential design as well as of the actual training of a generation of architects in the postclassical era. These Ivy League institutions welcomed the Europeans exiled from the Bauhaus on the eve of World War II, with Gropius and Breuer ensconced at Harvard and Josef Albers at Yale. Called "compounds" by Tom Wolfe in his caricatural and often inaccurate book From Bauhaus to Our House, there is still an element of truth in the idea of these modernist emigres holding court in these rarefied ivory towers. They proposed to overthrow traditional architecture, not only for the society at large but for the private home as well, achieving an ultimately ironic freedom from history as well as a slavery to the new style. No wonder many, including Norman Mailer and the editor of House Beautiful, called the new architecture for the home "totalitarian."

More than anything else, the great literary history of New England prepared the public and certainly the architectural community for the arrival of modern architecture. Through the authors Emerson, Thoreau, Herman Melville, and Emily Dickinson, the ideas of the inspiration of nature; the call for an authentic American expression in art, architecture, and literature; a desire for simplicity; the personality of the house; and the eccentric in the woods all allowed a place for the strange new architecture to be tolerated if not embraced when it arrived from the hand of Wright or European Bauhauslers. Important too was the change in attitude toward nature, from the Puritans' fear and desire to conquer to Emerson's beneficent view of it in his seminal essay "Nature" of 1836.

Emerson, a Transcendentalist and the foremost literary figure of the early nineteenth century, in his essays " Nature" and "Self-Reliance," called for an original American art and architecture. He was addressing the nineteenth century American and European problem of the recycling of styles, not only in literature but especially in architecture, which, despite new materials such as iron, steel, and glass, and new social programs, was trapped in a series of endless revivals of the past. Not only classical, but Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, even Egyptian were considered appropriate for the right job, be it a palace or a cemetery. Addressing this directly, Emerson wrote, "Our houses are built with foreign taste." Gropius then quotes Emerson's same essay in 1941, in his address entitled "Contemporary Architecture and Training the Architect": "And why need we copy the Doric or the Gothic model? Beauty, convenience, grandeur of thought and quaint expression are as near to us as to any, and if the American artist will study with hope and love the precise thing to be done by him, considering the climate, the soil, the length of the day, the wants of the people, the habit and form of the government, he will create a house in which all these will find themselves fitted, and taste and sentiment will be satisfied also."

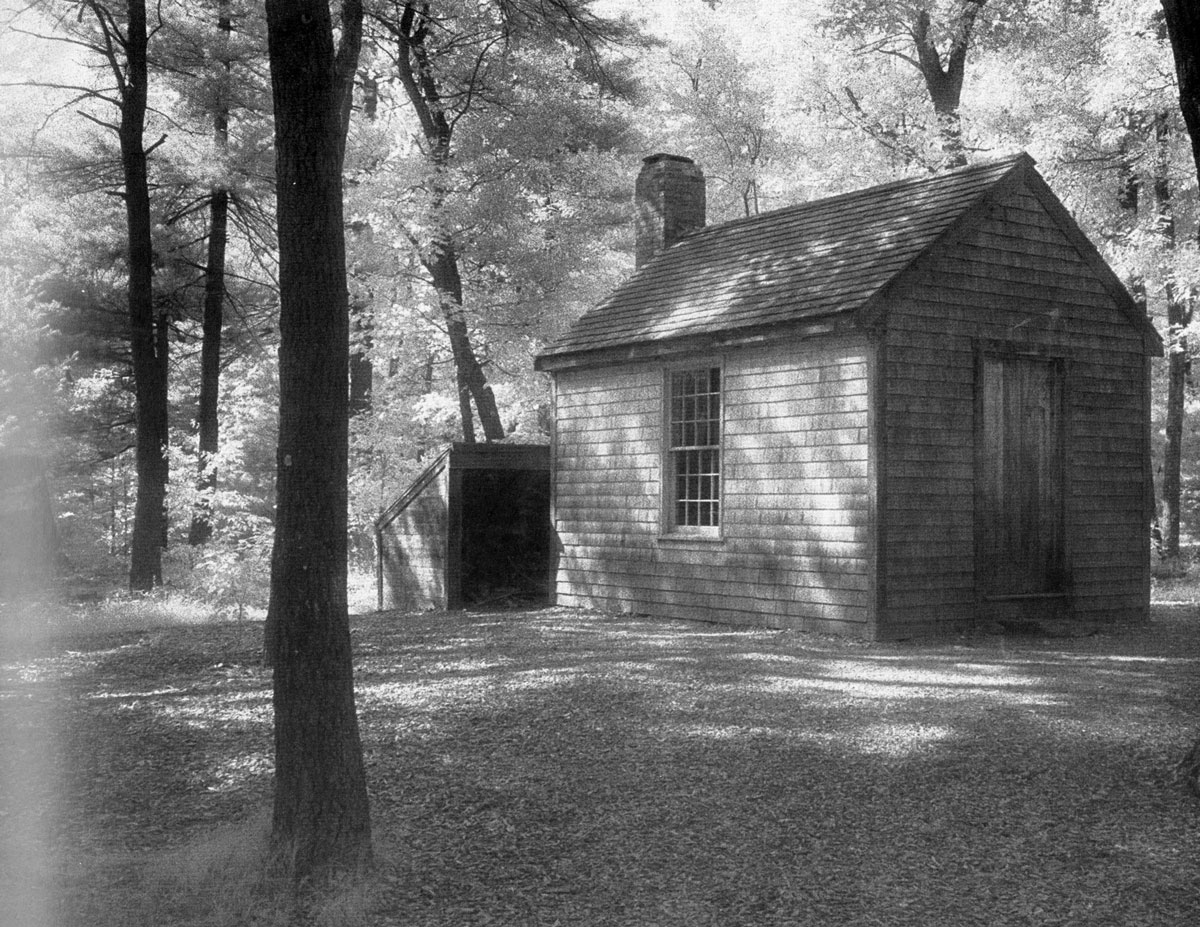

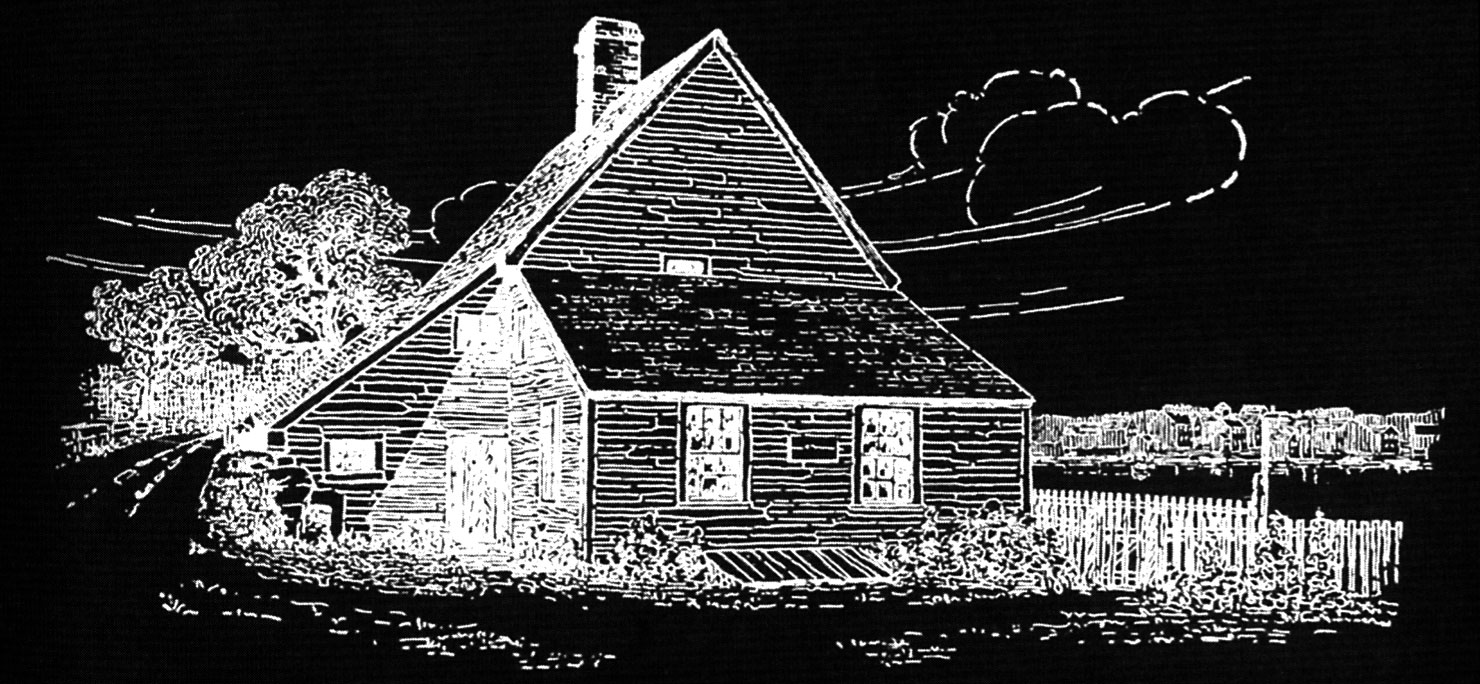

Henry David Thoreau's Walden; or, Life in the Woods is a neglected factor in the development of modern architecture in New England. The quintessential American eccentric, Thoreau chose to live alone and "off the grid" in a cabin, not in the wilderness but close to the town of Lincoln, Massachusetts. Thoreau went into the woods in 1845 to live "deliberately" and simply. His observations on life on Walden Pond, in a one-room house that he built himself, became one of the unacknowledged touchstones of modern architecture. Gropius made reference to Thoreau when he built his house less than a mile from Walden Pond. Architecturally, Thoreau's emphasis on simplicity and on the primacy of pure space over ornament predates Adolf Loos's seminal "Ornament and Crime" of 1908. Thoreau writes, "A great proportion of architectural ornaments are literally hollow, and a September gale would strip them off, like borrowed plumes, without injury to the substantials." And Loos: "We have outgrown ornament; we have fought our way through to freedom from ornament."

Of his 10-by-15-foot cabin Thoreau commented that "what of architectural beauty I now see, I know has gradually grown from within outward." This concept of architectural space growing from the inside to the outside recalls Frank Lloyd Wright's organic architecture and was expressed in the title of the recent Guggenheim retrospective "Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward." Thoreau goes on to describe the modern interest in the vernacular or primal house: "The most interesting dwellings in this country, as the painter knows, are the most unpretending, humble log huts and cottages of the poor commonly; it is the life of the inhabitants whose shells they are, and not any peculiarity in their surfaces merely, which makes them picturesque." Remarkably, he virtually predicts the arrival of the modern cubic houses in New England a hundred years later: "and equally interesting will be the citizen's suburban box, when his life shall be as simple and as agreeable to the imagination, and there is as little straining after effect in the style of his dwelling." There in a nutshell is all that the modernists sought to achieve in their own houses in the woods in the twentieth century.

Thoreau's description of living in a tent could easily pass for Philip Johnson's Glass House: "This frame, so slightly clad, was a sort of crystallization around me, and reacted on the builder. It was suggestive somewhat as a picture in outlines. I did not need to go outdoors to take the air, for the atmosphere within had lost none of its freshness." Even Thoreau's description of a more substantial idealized house makes the recent proliferation of McMansions seems as awkward as ever: "I sometimes dream of a larger and more populous house, standing in a golden age, of enduring materials, and without gingerbread work, which shall consist of only one room, a vast, rude, substantial, primitive hall, without ceiling or plastering... A house whose inside is as open and manifest as a bird's nest, and you cannot go in at the front door and out at the back without seeing some of its inhabitants."

Herman Melville touched on architecture in his rarely cited I and My Chimney, brought to the architect's eye by Vincent Scully. Here a man describes in a semi-comical manner his gigantic brick chimney, which threatens to engulf his entire house, much to his wife's horror. Many early colonial houses were exactly that, a series of rooms arranged around a single large fireplace. The harsh New England climate, within a periodic mini-ice age, demanded small windows and a large fireplace for warmth. It is an extended riff on a fight between the place of the hearth, a solid mass to contain the fire, which is dispossessing the living space of the house. "Sir, I look upon this chimney less a pile of masonry than as a personage. It is king of the house. I am but a suffered and inferior subject." In their dominance and centrality, Frank Lloyd Wright's fireplaces were of equal authority both in his Prairie houses and those set on New England soil.

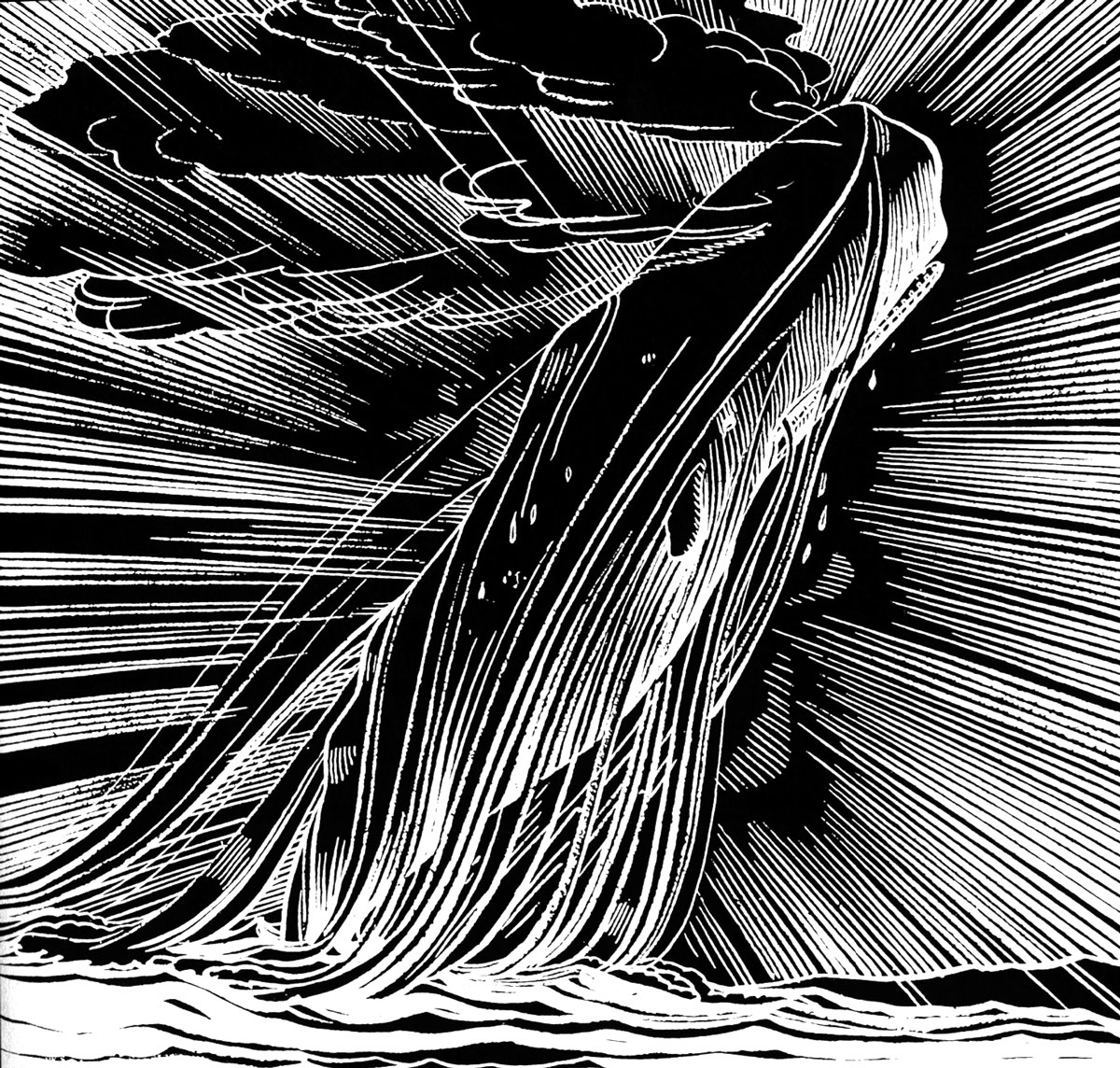

Yet it is Moby-Dick; or, The Whale that provides the strangest insight to two aspects of modern architecture in New England. John Hejduk, in his postscript to Richard Meier's monograph of 1984, cites Melville's chapter XLII, "The Whiteness of the Whale," to highlight this aspect of modernism and elevate it to the metaphysical realm. Since then, this chapter has become a kind of Freemasonic secret sign among design cognoscenti, an intersection of literature and the spirit of minimalism. Whereas Meier-author of the Smith House of 1967, in Darien, Connecticut, the ultimate modern house of New England says "whiteness is one of the characteristic qualities of my work," Hejduk quotes Melville to emphasize its mysterious qualities: "This elusive quality it is, which causes the thought of whiteness, when divorced from more kindly associations, and coupled with any object terrible in itself, to heighten that terror to the furthest bounds... Bethink thee of the Albatross, whence come those clouds of spiritual wonderment and pale dread, in which that white phantom sails in all imaginations? Therefore in his other moods, symbolize whatever grand or gracious thing he will by whiteness, no man can deny that in its profoundest idealized significance it calls up a peculiar apparition of the soul" Hejduk concludes his comments on Meier thus. "We too are strapped to Ahab's whale." We can read this comment both metaphorically and literally. Just look at the entry facade of Le Corbusier's Villa at Garches, recalling as it does the great broad head and monocular eye of a white sperm whale!

The International Style was also called White Architecture, as exemplified by Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye and work before 1930. The white cubes of Mediterranean villages were cited as vernacular confirmation of modernist architecture and planning. Gropius saw a confirmation of his modernist ideals in the nineteenth century image of the New England village arrayed around the green he showed his Harvard class a slide in 1940 entitled "Common of a New England village showing a well-balanced self-imposed order and unity which obviously resulted from a highly integrated team spirit of its community. In reality, the earlier Puritan villages of the 1600s were less organized, strewn about a muddy common, and darker in color because white paint was costly. As Arthur Miller wrote, "The meeting house was nearby, and from this point outward-toward the bay or inland-there were a few small-windowed, dark houses snuggling against the raw Massachusetts winter." It was not until after the exodus of farmers to the Midwest in the early nineteenth century that by intention the New England village came to take the shape that defined it in the imagination of the public.

Modern architecture was not just a style but a full-blown crusade, a term that happened to be the title of one of Le Corbusier's books. Crusades require allies and enemies. Ahab's quest for Moby-Dick was a perfect metaphor for the pursuit of an architecture of purity, whiteness, and global dominance. It corresponds with the dark side of the New England landscape, the witch hunt, and the whale hunt. And so the proponents of modern architecture crossed the Atlantic to a setting that would perfectly mirror their desire to destroy the traditions of the past in the process of creating a new architecture. As one of Gropius's students, Willa von Moltke, said, he loved New England architecture because it "compared to the Puritanical aspects of his own personality." Gropius was the Ahab of architecture, sailing the globe in pursuit of the great white International Style, the Scarlet "A" for Architecture branded on his grim black suit, doomed, like Hester Prynne, to bear the cross of the Bauhaus to his grave. With lip service to regional New England architecture and balloon framing, there was really precious little in common between the cozy colonial house and the chilly house he built for himself and his wife, Ise, in Lincoln, Massachusetts. But elusive as the whale was, so too proved to be the short-lived triumph of modern residential architecture in the Northeast.

From the early to the mid-twentieth century, modern architecture sought to establish itself as an expression of the time, invoking the zeitgeist, or spirit of the age, as a means of defending its abstract new forms and spaces. As opposed to the nineteenth-century parade of styles, its promoters considered it to be the culminating style of history, the "end" of architectural history, after which there would be only an ongoing contemporaneity, as philosopher Jurgen Habermas wrote in his essay "Modernity-An Incomplete Project." The immediate enemy was the academic Beaux-Arts-the fin de siecle efflorescence and subsequent denouement of classicism in its worst, most pastry-like confection.

As Gropius thundered, "We cannot go on indefinitely reviving revivals. Architecture must move on or die." There was a desire both in America, expressed through the work of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, and in Europe to create a new architecture for the new age. It would embody innovations in structure, social programs, and a strange fascination with the machine as somehow harnessing the forces of nature in a new way. It was most dramatically put forward by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in "The Futurist Manifesto": "We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty the beauty of speed. A racing car with its bonnet draped with exhaust-pipes like fire-breathing serpents-a roaring racing car, rattling along like a machine gun, is more beautiful than the winged victory of Samothrace." Hardly a theme for the design of the home, but nevertheless even the best of architects were seduced by the rage for the machine.

Although the machine was initially proposed as a metaphor for the solving of practical problems that resulted in beautiful form, soon an obsession developed for the actual forms of the machine itself. Modern architecture paid a curious homage to the machine and its various avatars: on land, sea, and air, the automobile, the ocean liner, and the airplane. According toLe Corbusier, these were machines that had solved the functional problems of their respective tasks, and in so doing also created as a by-product extraordinary forms that had superseded the classical language of architecture. In Towards a New Architecture, Le Corbusier famously even called the house "a machine for living in" and incorporated a "Manual of the Dwelling," an almost hysterical, exhortatory polemic calling for people to "demand bare walls in your bedroom, your living room and your dining room... Never undress in your bedroom. It is not a clean thing to do and makes the room horribly untidy... Demand a vacuum cleaner. Keep your odds and ends in drawers or cabinets. Every modern man has a mechanical sense." For a Frenchman, who should have at least a certain sensuality, Le Corbusier commands with the intolerant authority of a New England Puritan!

Of course, Le Corbusier was an extreme polemicist leading a revolution. But as a master architect he could design a house that could still be a poetic work of art, though it addressed machines and abstract form. In lesser hands the idea of a house as a machine became a dry exercise that ran anathema to the idea of comfort, the Gemutlichkeit, or cozy, sensibility that most individuals seek in their homes. Indeed there were ferocious contemporary critics of this vision, foremost among them Frank Lloyd Wright, who was strenuously against the machine as a model in any way for the home. In his essay "The Cardboard House" he wrote, "Human houses should not be like boxes, blazing in the sun, nor should we outrage the machine by trying to make dwelling places too complementary to machinery. Any building for humane purposes should be an elemental, sympathetic feature of the ground, complementary to its natural environment, belonging by kinship to the terrain." He goes on, "But most new modernist' houses manage to look as though cut from cardboard with scissors, the sheets of cardboard folded or bent in rectangles with an occasional curved cardboard surface added to get relief. The cardboard forms thus made are glued together in boxlike forms-childish attempts to make buildings resemble steamships, flying machines, or locomotives." According to Wright, a house should be fitted to its site and landscape, and not a cold, intellectual, Duchampran object type that could be located anywhere without modification.

However, already in the 1930s-and, ironically, shown at the very "International Style" exhibition that proselytized the white architecture-Le Corbusier's Mandrot House in southern France used rubble stone walls as its main construction material, completely at odds with the other sleek houses in the show. As William Jordy has shown, Marcel Breuer visited the house and incorporated rubble stone walls in his work long before arriving in New England.

The first modern house in New England was, surprisingly, an example from the Midwest traveling east, with an appearance from the Prairie School in 1912 by William Gray Purcell and George Grant Elmslie, followers of Wright, a full twenty-five years before the arrival of Gropius. The old master himself had lived in New England as a child in "a gray house in drab old Weymouth (Massachusetts)." Born in 1867, just after the Civil War, it is no surprise that Wright was called a nineteenth-century architect by Philip Johnson. Purcell and Elmslie's Bradley House, in Woods Hole, on Cape Cod, brings the Prairie-style celebration of the horizontal to a bluff overlooking the ocean and Martha's Vineyard in the distance.

The Prairie Style houses were Wright's heroic attempt to find a style that was intrinsically American, not transplanted from Europe. He looked to the site and landscape itself for inspiration, tying the house to the earth with a great plinth and enormous fireplace. He exploded the tight plan of the traditional house, with its cubicle-like rooms, into continuous and overlapping spaces, opening the corners on the diagonal to views of the landscape. Although, as Vincent Scully points out, he owes a debt to Henry H. Richardson and the Shingle Style of the late nineteenth century, Wright went much further to create an architecture that was fundamentally new. Using brick and, on the interior, wood, the houses were modern yet warm. The arrangement of rooms in the house plans were radical in so far as they allowed a family to live modestly and without servants; the kitchen was the center of the house, not hidden behind a nest of cooks' rooms. He called his ideas "organic" architecture a century before organic was certified as "green" and essential to the contemporary diet and lifestyle of the urban boho. But this, ironically, was Wright's Achilles' heel: his residential architecture was so far ahead of its time that he was written out of the early histories of modernism as a "nineteenth-century" figure. He was not initially associated with any of the European architectural schools of thought, such as De Stijl or the Bauhaus, even though he had influenced them. Wright was a loner, an American inventor in the wilderness of the prairie, and therefore could not be admitted to the pantheon of modern architectural pioneers.

Nevertheless, Wright did eventually build a number of houses in New England, although not until the early 1950s, long after the European emigres arrived on the scene. Wright's houses embody his postwar Usonian concept of affordable, modest homes that were still spacious and open to the landscape. Along with an entire community of Usonian houses in nearby Westchester County, the Zimmerman House in New Hampshire and the Rayford House in New Canaan were good examples of an alternative to the boxy white International Style homes that proliferated in Connecticut.

In Boston, before the arrival of Walter Gropius, Eleanor Raymond Was one of the first to build modern houses in Massachusetts, though she could not attend Harvard, as at that time the school was open only to men. Raymond was born in 1887, the same year as Gropius and Le Corbusier, and lived to 102. The house she designed in 1931 for her sister Rachel in Belmont was in the thoroughly modern International Style. Her second house was not as stylistically pure, but it did feature generally horizontal lines and clean interiors. The Raymond House was torn down in 2007.

Samuel Glazer also built a significant International Style house in 1936, in Brookline. However, it was not really until the arrival of the exiles of the Bauhaus that modernist residential architecture in New England took off with an evangelical fervor. Walter Gropius, the Silver Prince, as Paul Klee called him, was the founder and director, from 1919 to 1928, of the Bauhaus, then the leading modern school of design in the world. First established in Weimar, Germany, it had three homes during its fairly brief lifetime, including Dessau and Berlin. Originally it was more craft oriented but changed its emphasis to a synthesis of architecture, art, and industry. The Bauhaus was also distinguished by its extraordinary faculty, with Wassily Kandinsky and Klee teaching painting and Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe as professors of architecture. More than anything this demonstrated Gropius's ability to lead a school of powerful thinkers and led directly to his consideration for a position at Harvard. The Bauhaus was closed in 1933, shortly after the Nazis took power, and Gropius· left for London, where he was living when he got the call from Dean Joseph Hudnut at Harvard's Graduate School of Design.

In the mid-1930s Harvard's architecture school was teaching classical BeauxArts design, even though modern architecture was already in full swing in Europe. A good example of the late arrival of ideas to the "colonies" before news traveled instantaneously, Joseph Hudnut dragged the Harvard architecture department kicking and screaming into the present. He considered Mies van der Rohe for a professorship at Harvard, but after meeting the dour Mies he offered the position to Gropius.

Harvard in 1937 was not the liberal, progressive institution it is inclined to be today. It was an Old Boys' Club par excellence, a WASP, genteel gentleman's establishment that changed only in the 1960s and 1970s when women were admitted and quotas were dropped, even for jews as late as then. In fact, Hudnut needed to quash rumors of Gropius's being jewish: "Another statement repeatedly made about Gropius is that he is himself a member of a jewish family, or at any rate, has wide connections among jewish people. I do not consider these charges to be of any importance, even if they are true; but as a matter of fact they are not true. Gropius is a typical German of the scholarly university type." (30) In Ise Gropius's description of how she and her husband retrieved their belongings from Berlin, she casually mentions that a friend interceded on their behalf to Joseph Goebbels himself, appealing to the Nazi propaganda minister's sense of nationalism: Gropius had been selected in favor of the Swiss-French Le Corbusier.

Nevertheless, Gropius soon transformed Harvard into the leading architectural school in the United States, bringing such former Bauhaus colleagues as Marcel Breuer to teach alongside him. The Graduate School of Design attracted many of the future leaders of American architecture as students. Among them were I. M . Pei, Paul Rudolph, Edward Larrabee Barnes, Harry Cobb, Ulrich Franzen, and Philip Johnson. The curriculum was different at Harvard from what it had been at the Bauhaus, less ideological, certainly less socialist, and there were design studios devoted to the individual house, a luxurious problem virtually anathema in, Dessau.

Gropius was given a heraldic greeting upon his arrival in Boston, amusingly caricatured by Tom Wolfe in his book From Bauhaus to Our House. It included a generous offer from Mrs. James Storrow, a wealthy Boston patron, for a plot of land and a loan so that he could build his own house. This became a showcase of the new architecture as well as the venue for a salon devoted to the discussion of architecture, and in both senses it was a model for Philip Johnson's own house in New Canaan a decade later.

Based on his design for the so-called Master's House at the Bauhaus, Gropius designed his house of 2,300 square feet with his colleague Marcel Breuer, with whom he set up an architectural practice. It was located only a mile from Thoreau's cabin at Walden, a point made explicit by Gropius. He traveled throughout New England observing the white colonial houses and made an effort to relate to them in construction and sensibility. In 1939 the critic Lewis Mumford wrote in the guest book, "Hail to the most indigenous, the most regional example of the New England House! The New England of a New World." Whether these relationships to local traditional architecture were genuine or simply a means for Gropius to establish an American beachhead, he felt the need to soften the clearly radically different style for the cultural elite of the Northeast, for the house's flat roof and large panes of glass attracted attention for its similarity to gas stations and other industrial structures. Nevertheless the architectural historian Sigfried Giedion, in his monumental Space, Time and Architecture, wrote about it as if it were nothing new: "Yet neither its flat roof, its screened porch (though here designed to catch eastern and western breezes during the hot and humid summers), its vernacular weather-boarding (in which, however, the boards were laid vertically instead of in the traditional horizontal manner), nor its large windows could be said to make any notable divergence from the local New England building idiom."

A series of similar modern houses followed in Lincoln, including Marcel Breuer's own house and then a number of modern residential communities nearby. At Six Moon Hill in Lexington, twenty-eight modern homes were built on twenty-eight acres by Gropius's firm TAC (The Architects' Collaborative) in 1948. On Snake Hill Road, in Belmont, Carl Koch built eight modern homes in 1940, featured in the MoMA exhibition "Built in USA, 1932-1944." And there were the developments known as Five Fields and Conantum, named after the property owner written about in Walden, making literal the connection between modernism and the simple living of Thoreau.

Cape Cod, the weekend and vacation area nearest Boston, soon became the scene of much modernist experimentation. In Woods Hole was the Purcell and Elmslie Prairie Style house that, although a tour de force, did not catch on as a popular style in the area. Further up on the Cape, in an area virtually unchanged since Thoreau wrote Cape Cod in 1865, the impetus for the rise of modernism can be traced to jack Phillips, of the old New England family that established Phillips Exeter and Phillips Andover academies. Like Gerald Murphy, Phillips studied painting in France with Fernand Leger and became acquainted with modern architecture in the 1920s. He returned to the U.S. and built a house called the Paper Palace on the Cape, where Peggy Guggenheim, Max Ernst, and Arshile Gorky all briefly stayed. On his 800 acres, he invited a motley assortment of modern architects such as Serge Chermayeff, Breuer, Nathaniel Saltonstall, Oliver Morton, and Charles Zehnder to build houses. Although Phillips clearly could have built more elaborate homes, the Cape was not nearby Newport or the Hamptons, where budgets and lifestyles were more luxurious and elaborate.

These were vernacular modern structures, inspired as much by Cape Cod slanted-roof "saltboxes" as by modernist allure with ships and structure. The rustic modern house of Chermayeff was one of the most remarkable, cross-braced with colorfully painted panels anticipating Le Corbusier's Heidi Weber Pavilion of 1967 in Zurich. The Hatch House by Jack Hall is one of the purest examples of an abstract cubic grid with a vernacular flair In the end, a significant assortment of modernist heroes summered and built here. In 1961 the Cape Cod National Seashore was established, preserving a great deal of the unspoiled Cape but threatening many of these modernist houses, which were now on federal land and had to be leased back every twenty-five years. Recently Peter McMahon founded the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, which has done wonderful work restoring a number of these houses and disseminating information to gain wider awareness of their cultural importance.

Nestled in the hills of Connecticut at the end of the commuter rail line lies New Canaan, its name resounding with the biblical promise of a land of milk and honey. Like the Puritans in search of a fertile land to put down roots, postwar modern architects found New Canaan to be a welcoming place to explore the new architecture. Most were graduates of Harvard's Graduate School of Design, and in 1947 Eliot Noyes was the first to move to town It made sense for a number of reasons: it was the proverbial one hour from Manhattan, land was reasonably priced, and a young architect could even build his own house. He was soon joined by Philip Johnson, Landis Gores, Marcel Breuer, John Johansen, John Black Lee, and Victor Christ-Janer. They descended upon this defenseless town to either contribute or inflict their ideas, depending upon one's stylistic point of view. Many of the houses were as close to each other as those in John Cheever's "The Swimmer."

Philip Johnson arrived in a rather roundabout fashion. After his "International Style" exhibition at MoMA in 1932, and of course before the United States entered the war, Johnson flirted with the other side, so enamored of Hitler and leather-clad young men that he was "embedded" with the German troops on the blitzkrieg through Poland in 1939. This would all seem beside the point, but there he observed the "burnt wooden village I saw once where nothing was left but foundations and chimneys of brick," which he literally cited as an inspiration for his New Canaan Glass House of 1949. Besides allowing close proximity to his fellow Harvard graduates for camaraderie and support, the house's location was also fairly close to the Rockefeller estate at Pocantico Hills, attracted as he was like a moth to the enlightened well-to-do, especially the Rockefellers, who had founded the Museum of Modern Art. He bought the original five-acre site on Ponus Ridge and two years later, after an arduous design process, completed what would become the most notorious of modern houses, his Glass House. Unlike anything seen in New Canaan, the glass pavilion attracted the curious by the thousands, who lined the street to catch a glimpse of the novel structure.

Among the earliest modern houses in the region were Marcel Breuer's, with its cantilevered porch, Eliot Noyes's floating white boxes, John Johansen's own cubic house, and Landis Gores's hovering roofs inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright. Most of these houses were built by architects for themselves, as showcases for their work and the new style of architecture. (This was completely different from Europe, where the emphasis was on social housing built by the government.) Soon New Canaan became a virtual vortex of modernist thought, attracting both positive and negative attention for the realization of these radical houses en masse.

Johnson offered the most extreme version of new way of living, a unique house for a single, wealthy gay man. It is a house of paradoxes- as Frank Lloyd Wright said when visiting, "Do I take my hat off or leave it on?"34 It is open to nature yet apart from it, framed by cold glass walls that are sinister at night, when they become black screens. Eliot Noyes's second house was a fortress in the woods facing the street. A great stone wall recalled old farm walls and created a private interior court completely open to nature. On each side of the open courtyard were public living areas separated from the bedrooms by a covered walk. Since the climate was less southern California and more. Scandinavia, a great fireplace sits at the center of the living room, managing to impart a cavelike quality to the open pavilion.

In hindsight, most of these experiments were comparatively small, less than 2,000 square feet, half the size of a typical house of today and not even remotely the size of contemporary luxury homes in Connecticut. The bedrooms and bathrooms were generally sized for the ideal "minimalist dwelling" of social housing and would not pass muster today. Their only luxury was their openness to the surrounding forest, made possible with large panels of glass and outdoor terraces. As local interest grew, in 1949 the first modern-house tour was organized as a charity benefit, attracting a thousand visitors and enormous publicity to New Canaan. As the new pilgrimage to the modernist Mecca, the biannual tour was a great success in establishing New Canaan as a center for progressive residential architecture.

Apart from the admiring throngs of architectural pilgrims, the local reaction was more mixed. Indicative of the country club ambience of New Canaan, it took the form of a polite series of "poems" sent to the New Canaan advertiser. The alias "Ogden Gnash Teeth" wrote disparagingly that Noyes, Breuer, Gores, Johansen, and Johnson have graciously condescended to settle here and ruin the countryside with packing boxes. "And partially opened bureau drawers set on steel posts and stanchions .. An architectural form as gracious as Sunoco Service stations."

Of course for a modern architect that would be a compliment; in fact two gas stations take pride of place in Johnson's own International Style book, before any of the houses that he shows. Despite Frank Lloyd Wright's objection to the "Cardboard House," and although he designed an organic modernist house in town in 1956, the image of the abstract, boxy white house dominated the public's perception of New Canaan modern architecture.

The late 1940s and early 1950s began a monumental debate for the hearts and wallets of the postwar citizen. Much was at stake, not only the theoretically correct aesthetic of architecture, but also the billions of dollars that would be spent building homes for returning veterans. The forces of modernism were led by the Museum of Modern Art: in the catalog for its exhibition "Built in USA, 1932-1944," Alfred Barr proclaimed, "the battle of modern architecture in this country is won," a victory perhaps premature considering the trajectory of history afterward. In 1949 the museum actually built an entire house by Marcel Breuer in its garden as a model of the home of the future. Its butterfly-wing roof and spacious interior contrasted surreally with the surrounding Midtown skyscrapers.

Elizabeth Mock's book If You Want to Build a House, published by MoMA in 1946, actually begins with a quote from Emerson's "Self-Reliance: And why need we copy the Doric or the Gothic model. Insist on yourself, never imitate." She accurately states that "modern architecture isn't that easy," and goes on to demonstrate how each room of the house will be affected by the new emphasis. on light, openness, material, and siting. She assures the reader that within a few years no one would be living in traditional houses of any kind and that modernism would triumph as the authentic style of the present, just as each of the historical styles--classical, medieval, colonial-represented their own time. Unusual in a MoMA publication of that time, Mock uses many examples from Frank Lloyd Wright's houses, which were warmer, more domestic, and more discreetly set into the landscape than many of the International Style spaceships.

Finally, George Nelson and Henry Wright's Tomorrow's House, published in 1945, was perhaps the most extensive of these domestic propaganda screeds. Comparatively mild compared to the revolutionary and dictatorial style of Le Corbusier's writings, this book nevertheless proclaimed that the modern American house would without doubt supersede all styles of the past that Americans had previously loved: "In designing houses today we have to be ourselves twentieth- century people with our own problems and our own technical facilities. There is no other way to get a good house. No other way at all." The authors start off with the warning that if you own the latest refrigerator and car but live in a colonial house, this book is not for you. They go on to describe a misguided young couple who build a traditional house, but since the moldings don't show any sign of age they run around knocking them up with a "heavy set of keys." This faux sensibility is indicative of timid souls rather than a contemporary authenticity encouraged by the authors.

Both Nelson and Wright are confident that the public will soon be "sold" modern architecture: "The Colonial dream is approaching its end. How do we know? In two ways. We have been watching the advertisements, the movies, and the magazines, and the swing to modernism has definitely begun. All of our tremendous apparatus for influencing public opinion is tuning up for a new propaganda barrage in favor of these new houses. A new fashion in homes will be created, and the public will follow." The public will follow just as it did with cigarettes, cars that were unsafe at any speed, and whatever else Madison Avenue was paid to sell. Both Mock and Nelson and Wright's books predict "enormous" changes in the way we live but fail miserably to identify them except for the invention of the "family room," an unprogrammed space for multiple activities. One longs for the brutal clarity of Le Corbusier's blatant propaganda in Towards a New Architecture. Most of Nelson and Wright's arguments reduce each room to a functionalist flow chart, as if they were designing a traffic pattern for a highway rather than a home for people-for example, a kitchen is called the "work center" And Frank Lloyd Wright had already opened up the plan in the Prairie Houses circa 1900, with a compact kitchen, dining room, and living area not requiring servant rooms. Resistance to modern architecture for the home came from a variety of sources, including Emily Post, known for her books on etiquette as well as her monumental The Personality of a House of 1939 Out of 540 pages, exactly are devoted to the "The Style We Know as Modern." Writing as if for today, she hilariously and accurately divides modern architects into categories, including Idealistic Moderns ("that alone is Modern which has never been expressed before"); Distortionists (who "simply deform beyond recognition whatever objects come to hand It is these...who give to Modern design its examples of illiterate and decadent vulgarity. Everything they make is overstuffed or under spindled, queer in shape-in short, freak"); and Ego-Modernists ("These comprise the third and most diverting class, since they seek to express themselves nothing else in the world! If you are an Ego-Modernist, you simply interpret yourself-either as you are or as you would prefer to be.") And all this long before the likes of Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, and Rem Koolhaas, who would stretch the ego category to its limit!

Among the ranks of writers for the popular shelter magazines, Elizabeth Gordon, editor-in-chief of House Beautiful from the 1940s to the 1960s, railed in 1952, "The much-touted all-glass cube of International Style architecture is perhaps the most unlivable type of home for man since he descended from the tree and entered a cave."44 She called it "The Threat to the Next America," as if there were some kind of conspiracy, going so far as to imply a Communist plot against capitalism: "They are promoting unlivability, stripped-down emptiness, lack of storage space and therefore lack of possessions." She decried the "dictators in matters of taste and how our homes are to be ordered." Her position was echoed years later by Norman Mailer in 1964 in Esquire magazine: "Totalitarianism...has haunted the twentieth century...And it proliferates in that new architecture which rests like an incubus upon the American landscape, that new architecture which cannot be called modern because it is not architecture, but opposed to architecture. This new architecture, this totalitarian architecture, destroys the past."

Ironically, modern architecture, originally promoted as the apotheosis of individualism, was now equated with totalitarianism, even after the Bauhaus was hounded by the Nazis and its faculty embarked for America. Also working against the triumph of modernism was the authoritarian and inquisitorial nature of the movement itself against the slightest infraction of its Puritanical code. Like Saturn devouring his children, the modernist establishment met every apostasy with expulsion from the club. This was the fate of J.J.P. Oud, a hero of the International Style. After he decorated the Shell headquarters in postwar Holland with neotraditional ornament, he was unceremoniously dropped from the pantheon of modernists by Philip Johnson. The same happened to Edward Durell Stone, most dramatically, to Morris Lapidus, who, after the blasphemy of the French Provincial interiors of the modernist Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami, was virtually banished from the architectural press. The final blow came from the very apostle of modernism itself, when Philip "Judas" Johnson betrayed the cause in an increasingly historicist pastiche of the past culminating in the Chippendale-topped AT&T Building in New York. If Philip changed his spots, who else could resist?

On the residential front, the ship of modernism ran smack into the conformity of the 1950s. It was not acceptable to be different in most aspects of life, so why on earth would one build a modern house, the most conspicuous presentation of the self in a suburban setting. It was the time of TV's Leave It to Beaver and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet; the conventional nuclear family was the ideal of the time. It is no wonder that modern architecture did not catch on.

Authors of modern house books such as Elizabeth Mock and George Nelson, with their pseudo-rationalist explanations of a new way of living, completely leave out the multilayered complexities of suburban life in the 1950s: the constant threat of nuclear annihilation, the cold war, the nascent civil rights movement, the repressed desire of women for a more meaningful life or at least the option for one, the hidden gay world, the dependence on the car, and the concomitant isolation of families in their separate homes. All of these reflect the inability of the architect to do more than present a new "style" rather than explore in depth a design that would truly allow for more than superficial changes in living.

Only an urban setting afforded the anonymity to march to a different drummer. Although the modern style appeared to be radical, the conservative nature of architecture remained dominant. All the architects were middle-aged white men, and women were "housewives." As Bernard Rudofsky wrote in 1955, "Nevertheless, men still make the major decisions on the house and, to this day, architecture is a man's business." Philip Johnson did not come out as gay until he was ninety-five. The individualism and self-reliance inspired by Emerson met the new Puritans of the 1950s, leaving only Thoreauvian eccentrics in the woods of New Canaan and Cape Cod. Only recently have these paradoxes of the time been explored in popular media, ranging from Todd Haynes's revisionist melodrama Far from Heaven to the wild contradictions of the television series Mad Men.

It is with extraordinary irony that not only did modernism fail to catch on as the style of houses in New England (or anywhere else, for that matter), but also that these houses, which were trumpeted as the houses of tomorrow, are now themselves historical relics. Many were until very recently in danger of being torn down and replaced by McMansions of the very Colonial and Georgian styles that they were meant to replace. Even contemporary architects are not always sympathetic to the scale and proportion of the originals when they renovate modernist houses. Nevertheless, these houses represent a unique and valuable era characterized by enthusiasm, passion, and optimism. It was a creative time in a special place of experimentation with new plans, materials, and spaces, taking ideas from Europe and adapting them to the local climate and landscape and building techniques. But memory is not enough. The purpose of this book is to help highlight these houses so that their value both as objects of art and a memorial to a time long past will be newly appreciated.