The Sistine Chapel Restored - Interior Design

In one of the world's most famous interiors, Michelangelo's frescoes are being returned to their original-and-unsuspected-color and clarity.

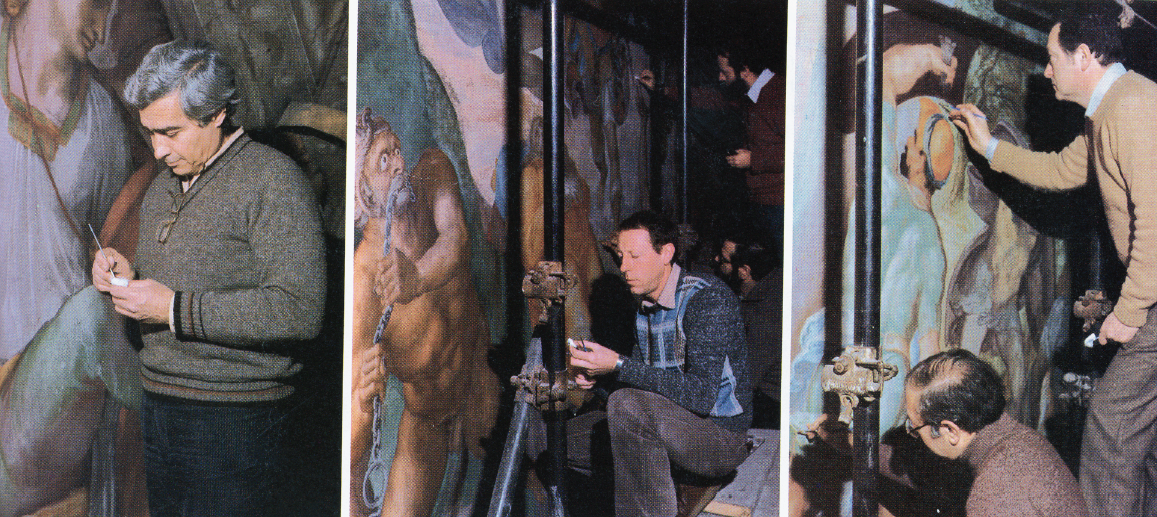

Hidden behind a sixty-foot curtain in the Sistine Chapel on an elaborate construction of scaffolding, a twelve-year documentary is being filmed by a Japanese TV company. For the first time in centuries, Michelangelo's frescoes are undergoing a restoration and cleaning that has revealed stunning colors and bold brushwork vastly different from their previously murky aspect.

After four years of painstakingly slow work, the cleaning of the fourteen lunettes is almost complete. These are the semicircular areas above the windows of the Sistine Chapel which include Michelangelo's portraits of the ancestors of Christ (as named by St. Matthew) and which form the base of the ceiling. This is the first part of a three-stage process that will later include the ceiling and finally the large wall painting of the Last Judgment. While Michelangelo painted the ceiling and lunettes in four years, 1508-12, the present cleaning will take twice as long. The entire restoration is expected to be finished by 1992.

In the complex financial world of the Vatican Museum, Nippon TV of Japan is paying $3 million over twelve years for the restoration in exchange for exclusive photographic rights. A series of documentary specials has been planned and the first was seen in Japan this February. In 1981 Pope John Paul II, during his visit to Japan, approached Chairman Kobayash of NTV and Japan's largest newspaper chain with the idea of funding the restoration. The Pope reportedly also consulted with NBS TV in the USA but decided instead to award the contract to the Japanese.

The Sistine Chapel was the Pope's personal ceremonial chapel and is still used by the conclave of Cardinals during the election of a new Pope, traditionally signified by a puff of white smoke from the chimney. The initial restoration of the chapel began in 1965 with the cleaning of the lower side walls, painted by such 15th century artists as Botticelli, Signore Perugino, and Ghirlandaio. In over 450 years the frescoes had accumulated many layers of soot and dirt from candles and torches. In addition the roof of the chapel had been leaking for hundreds of years, causing a network of cracks n the scenes of The Creation and also tough films of calcium carbonate to form over the paint. It was not until as late as 1975 that the roof was finally repaired, the tiles replaced, and a catwalk installed in the attic over the vault of the chapel. Until then to gain access to the attic it was necessary to walk directly on the vault, the underside covered with Michelangelo's fragile frescoes subject to the slightest vibration, The previous single most damaging event to the ceiling occurred in 1797 when a gunpowder explosion in the Castel Saint ‘Angelo more than a quarter of a mile away caused a powerful compression of air that knocked down a large portion of the painted surface surrounding the scene of The Flood.

There is presently a study being conducted by the Central Institute of Restoration in Rome to change the air flow in the chapel to lessen the effects of heat, humidity, and dirt from the outside. However because of the cost, there are no plans to air-condition the hall. Lighting of the ceiling however will be improved.

According to Dr. Fabrizio Manchinelli, Curator of the Vatican Museum, this is only the third time in its history that Michelangelo's work has been cleaned. After the Last Judgment was finished in 1541, a man called a mondatore was hired to keep the frescoes clean by peeling off hardened dirt. Aside from these periodic cleanings, the first major restoration was done around 1635 by a restorer named Lag who actually rubbed the frescoes with bread rolled into balls. As strange as it sounds the bread apparently worked efficiently as an eraser, the dust being then more powdery and more easily removed than now.

The second cleaning was done n the early 18th century by the Baroque painter Carlo Maratta (1625-1713) who repainted certain parts of the frescoes, such as the left foot of Eleazar in the lunette At this time Michelangelo's colors were still vivid as Maratta stones match the original in the newly cleaned areas. Afterwards, retouchers simply imitated the dirty colors they saw Major problems were created n the 19th century when restorers, instead of cleaning the frescoes, coated the surface with animal glues. This gave the paintings a wet lacquered appearance seeming to penetrate through the grime. However the glues soon yellowed and cracked and the brushstrokes of the aging glue began to be confused with the strokes of Michelangelo. Fortunately, the greatest percentage of damage has not been to the frescoes, but to these glues applied on top, according to Professor Gianluigi Colalucci chief conservator of paintings at the Vatican and the official responsible for the restoration.

The cleaning procedure is essentially very simple and has been used successfully before in the restoration of Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. The area to be cleaned is first dusted with a soft cloth then gently wiped with distilled water. Finally a chemical so vent, AB57 s brushed on and removed n periods of time varying from 3 minutes (where the layer of dirt is light) to 45 minutes (to work through calcium deposits where water had leaked through the ceiling Time is a crucial factor thus Colalucci is careful not to leave the chemical on too long and to leave a thin film of dust on the painting as a shield against air pollutants. AB57 was originally created for marble but was found to work as well on frescoes. One of its ingredients is xanthum gum also used as a thickener in salad dressing.

Where cracks in the plaster reveal that the paint surface had become detached from the wall a casein glue called Vinnapas (similar to Elmer's glue) is injected with a hypodermic syringe into the area behind to reattach it to the wall. This process is a great advancement over the 1930's when half the vault was consolidated with a thick Iyme and marble paste that required the drilling of large hoes to insert the substance visible in the photograph of the Ozias-Joatham-Achaz lunette.

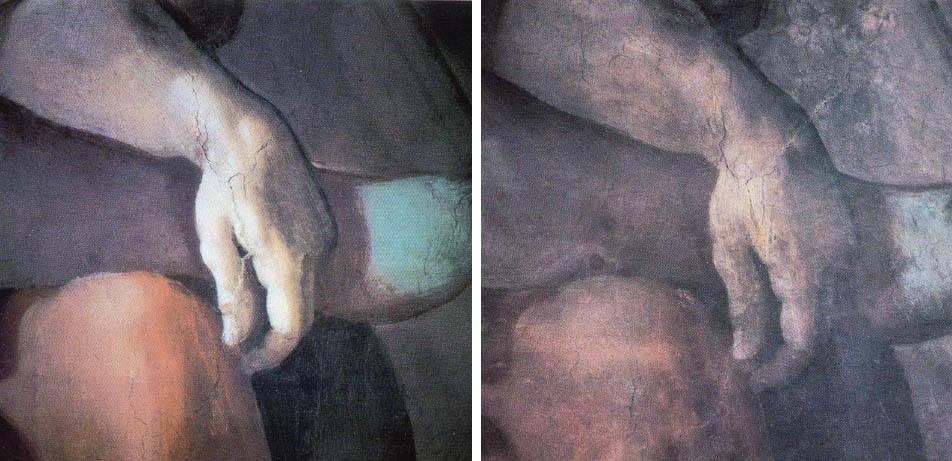

Michelangelo at first resisted the commission by Pope Julius in 1506 to pant the ceiling not starting until 1508 insisting that, "This is the difficulty of the work, it not being yet my profession." He had done little panting before this and was almost exclusively a sculptor. At first, he had trouble with the fresco technique; mold developed and some sections had to be repainted. But by 1510 Michelangelo had mastered the technique and form to the extent that the lunettes were painted with enormous speed in furious strokes (sometimes hairs of the brush remain in the plaster) each in only three days. And the cleaning has revealed that they were done without any cartoon (large scale outline) as there is no evidence of incised lines or dots in the plaster surface. These large figures, over seven feet high, were therefore painted freehand with only the slightest painted sketch beneath as a guide.

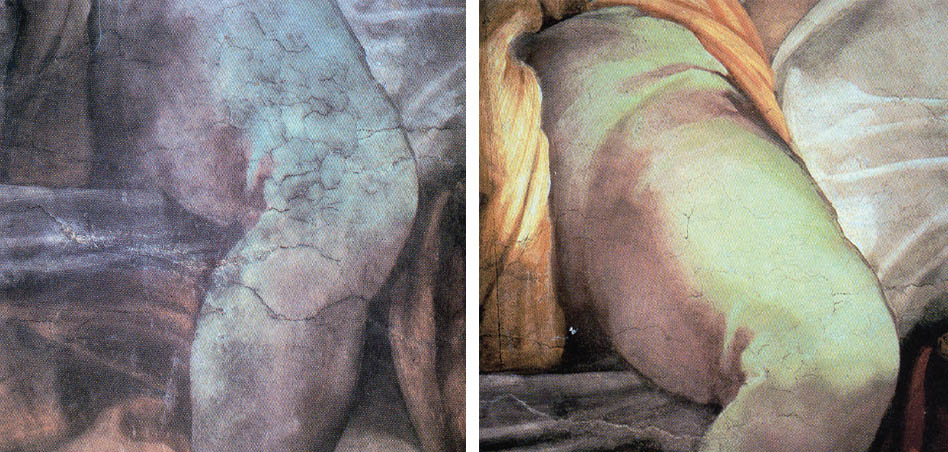

The surprising discovery of brilliant and luminous colors beneath the centuries of dust has completely changed art historical conceptions about Michelangelo's use of color. The lunettes especially were considered to be an area of shadow with figures barely emerging from the darkness. Color was considered secondary in the conception of the ceiling as seen in the following quotes: "He ignored all that concerns color," Roger de Piles, 1699. "All this vault is without effect the color verges on brick and gray," M De Lalande, 1768. "Color would greatly impair that work, it would cease to be the mental vision of a fact that is above human concepts," G B Nichol, 1825.

As Manchinel points out, Michelangelo constructed form in layers, starting with a dark ground to which is added shimmering surfaces of lighter color applied in great washes. Up close, the watery colors appear more like great sketches, unfinished in delta but powerfully capturing the essence of the form with the most economical of means. Meant to be seen at a distance from below the great sea of the figures and the vibrating acid greens, violets and oranges form an enormous contrast to the Botticelli is below in which every hair is painted with extreme precision in the end the misunderstanding of Michelangelo’s color derives from the false impress on of the dark areas which were the result of dirt, not intentional chiaroscuro.

Manchinel believes that the holes for the sorgozzoni prove that as Vasari and Condiv biographers of Michelangelo, imply the scaffolding did not have supports on the ground so as to avoid obstructions and was constructed in such a way to permit work to be done on every part of the ceiling including the lunettes. In effect, a wooden truss bridge was built spanning the vault and resting on the supports inserted in the holes. The rough plaster strip Michelangelo was unable to paint was thus blocked by the location of the bridge. Colalucci plans to avoid the pain Michelangelo endured as he painted the ceiling expressed in his poem of 1510, "I’ve got a goiter from the strain and I am bending like a Syrian bow." A flexible reclining seat is planned for the restorers this time for more comfort.

As the work on the lunettes draws to a close, the scaffolding now adjacent to the Last Judgment affords extraordinary views of the unfortunate souls being thrown into Hell. The TV crew is busy filming the process, and it is clear that in their financial commitment to the restoration the medium has again ceased to be a passive recorder or news and has become an active participant in the creation of events. Starting with Michelangelo who himself fostered the myth of the superhuman creator to Charlton Heston in The Agony and the Ecstasy it is not the work itself that takes center stage, unveiling spectacular effects of color and light that have lain unseen and unsuspected for centuries.